Team Babylon! 💣 CS 175: Project in AI (in Minecraft)

Video:

Project Summary:

Our project’s aim was to create Malmo agents that would learn to fight different enemies using Q-learning. In addition to training the bots in combat, we hoped to compare the performance of two different bots, a General Bot and a Specialist. The main difference between these two bots is that the General Bot learns a combat strategy independent of the type of enemy that it is fighting, while the Specialist learns a combat strategy specific to each mob type. Our hope was that the General Bot would show an improvement over a naive bot, and that the Specialist would show an even greater improvement than the General Bot. We believed this because with its more specific world state, accounting not just for position, health, and weapon, but also the type of enemy, the Specialist would learn to tailor its combat to a certain mob type.

For the most recent update to our project, our group focused on expanding the state space, and along with it, the abilities of our bot. The main focus here was the ability to use both the bow and the sword, and switch between the two as the bot saw fit during combat. Given the increase in the number of possible actions, specifically those focused on attacking, we felt it was limiting for the bot to have to decide between either a movement action or an attack action. We therefore have implemented a dual Q-Table system, in which the bot associates rewards with both an attack action and a movement action separately, so they can be executed simultaneously, rather than having to decide between one or the other.

Approaches:

Our approach towards machine learning was to use Q-Learning and state tables to train the agents. For each fight, we set up an arena and spawn an agent and a single enemy. Using the world observations provided by Malmo, we calculate the enemy pitch and yaw in order to ensure that our agent is always facing the mob. Forcing the bot to aim at the enemy is the only real guidance given to the bot. The rest of its actions are chosen using Q-Tables. We trained our bots against 12 enemy types: blaze, creeper, cave spider, endermite, ghast, silverfish, skeleton, spider, wolf, witch, zombie, and zombie pigman. In addition, each bot was trained for 10 rounds, where a round is an individual fight against each mob type (10 rounds = 120 fights total, 10 per enemy).

Q-Learning:

Q-Learning Pseudocode:

Q-Table Update Equation:

Q-Learning Paramters:

ε = .2: The probability of the agent taking a random action (during learning only)

α = .3: The learning rate of the agent

n = 10: The lookback number, previous steps to update given current reward

-we set this number somewhat high in order to encourage full bow extension

and associate chains of actions with higher rewards

γ = .9: The decay rate

-Some research (which was later reinforced by our own observations) showed

this to be an effective number for increaseing the likelihood of converging

on an optimal strategy

State Space:

As mentioned above, we trained two different bots: our General Bot and our Specialist. The General Bot’s world state is made by taking three different observations: the current distance from the mob, the current health of the agent, and the current state of the weapon. As the measurement of distance is continuous (and therefore nearly infinite) and health can be broken down into 21 different states, a state space using these two alone would be prohibitively large for an agent to learn. To make the state space usable by Q-Learning, we discretize the two variables into the following categories:

Health: { h <= 2: 'Low', 2 < h <= 12: 'Med', h > 12: 'Hi' }

Dist: { d <= 2: 'Close', 2 < d <= 4: 'Melee', 4 < d <= 20: 'Bow', d > 20: 'Far' }

Finally, as we added bow functionality to this most recent version of our project, we needed a state to track the weapon we are using, and when we are using the bow to track how close it is to full extension. We therefore have several weapon states:

Weap: [ 'sword', 'draw 1', 'draw 2', 'draw 3', 'draw 4', 'draw 5', 'fire' ]

During the main loop, our bot chooses a new action every 200 ms. As the time taken to draw the bow to full extension is 1 second, this gives us the 5 ‘draw’ states. This brings the state space to a total of (3 x 4 x 7) = 84 different possible states. However, this is only for the General Bot. The Specialist, which is an extension of the General Bot, has an extra state associated with each of the possible general states, specifically the type of enemy. This increases the Specialist state space by a factor of 12, bringing it to 1008.

Dual Q-Tables:

An important aspect for our recent efforts on our project was the added use of the bow. Rather than simply making ‘fire’ a single discrete action, we wanted to give the bot the ability to learn how far to extend the bow on its own. This led to a large increase in the attack action space of the bot, and because moving and attacking were part of the same possible actions list, it was forced to decide between one or the other. As we wanted a bot that could both move and attack at the same time, we decided to train two separate Q-Tables, one associated with movement actions, the other with attack actions. While the state space is the same for both (described above), the possible action list is very different. From any given state in the movement Q-Table, the possible actions are the same:

Movement Actions: [ "move 1", "move 0", "move -1", "strafe 1", "strafe -1" ]

This gave the bot the ability to move in any possible direction, from any given state, or choose to stand still. The attack action space is state dependent. While holding the sword, it can choose to attack or switch to the bow. If it is holding the bow, each state’s given actions are to move to the next draw state, or to fire the bow early. Finally, when the draw reaches ‘draw 5’ the only possible action is ‘fire’.

Rewards:

Our reward function is very straightforward. Each time we take an action, we check the world observations for the enemy health and the agent health. If there is a change in agent health we are penalized our change in health times 10. If we have dealt damage to the enemy, we are rewarded the difference in health times 15. If there is no change, to either, we are rewarded -1.

By putting a greater weight on enemy health, we attempted to make the bot prioritize doing damage as opposed to maintaining health.

As the difference in the enemy health is a useful way of determining a reward for combat, we thought this feature was a vital part of the program. Unfortunately, when we began working on this there was no method for obtaining the enemy health from the observations. In order to add this capability, one of our team members modified the Malmo code based and became a contributor to the Malmo repository, adding this feature for our group and any other group that may need it.

Evalutaion:

After running each bot for 10 learning rounds (120 fights, 10 per enemy type), our bots seemed to have found their optimal strategy. We then decided to run them for 10 rounds making only optimal decisions. While ten may seem a small number of data points to make an accurate assessment of the bot’s performance, the variance in data between trials is fairly low for most mob types. We therefore decided that this would be an adequate number for a quantitative evaluation of the bots.

As a baseline, we ran a “Dumb Bot”. This is in essence the General Bot with its epsilon value set to 1 so that it always takes a random action regardless of the optimal strategy. This was meant to establish the performance of a bot that did no learning at all. We were somewhat surprised to find that this bot often still managed to kill its enemies. However, this can be attributed to the fact that after separating the Q-Tables for movement and action respectively, the bot always chose some attack action. In addition, because using the bow makes up a larger portion of the action space, it is much more likely to be in a state from which it will fire its bow. Therefore, regardless of not choosing optimally, it is generally attacking in some form and may still best the enemy.

As far as qualitative observations go, a distinct difference can be seen in the strategies of each bot. As seen in the video, the Dumb Bot will generally move in a random direction, and in addition often fires arrows before the bow is fully drawn. While this can be effective against some enemies, it leads to inconsistent results even when fighting the same enemy. The General Bot shows a noticeably consistent strategy, preferring to stay at a distance while firing the bow at or near full extension while slowly moving forward. In addition, while not clearly shown in the video, when it gets near an enemy it prefers to strafe while swinging its sword. Finally, the specialist had an array of different strategies for each enemy type. For things such as the endermite and silverfish, small and fast moving mob, it preferred to fire the bow not at full extension while slowly inching backward. For most types, it learned a strategy similar to that of the General Bot, firing from a distance and moving closer to the mob. The most interesting and noticeable difference was its method for killing Ghasts. It learned to charge at it while swinging the sword, presumably to deflect the Ghast’s fireball back at it, which results in an instant kill. While not always successful, it shows a clear difference in strategy to that of the General Bot, and to its other methods of fighting mobs.

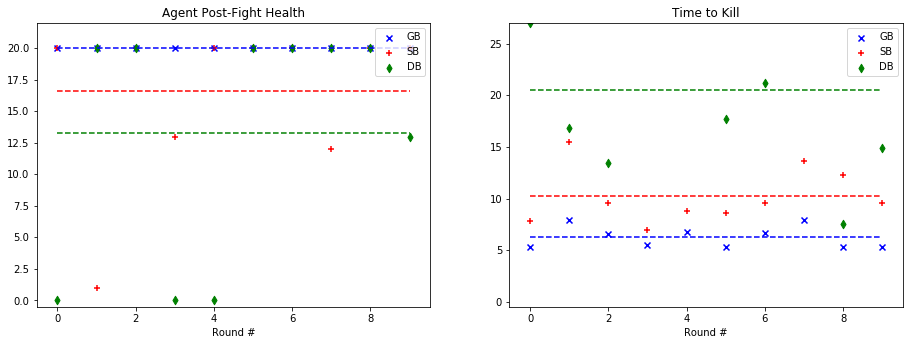

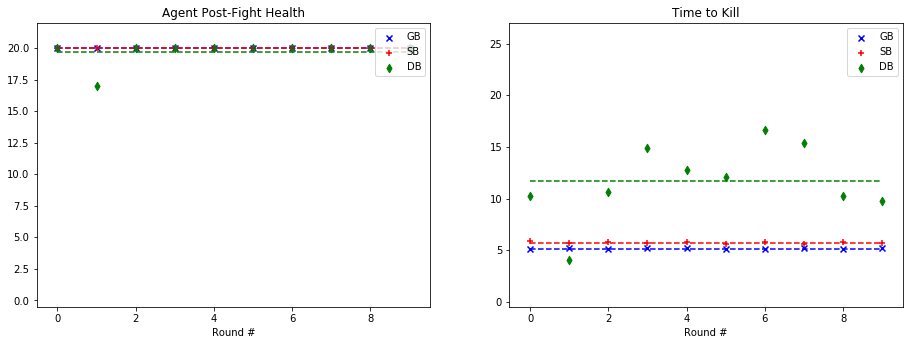

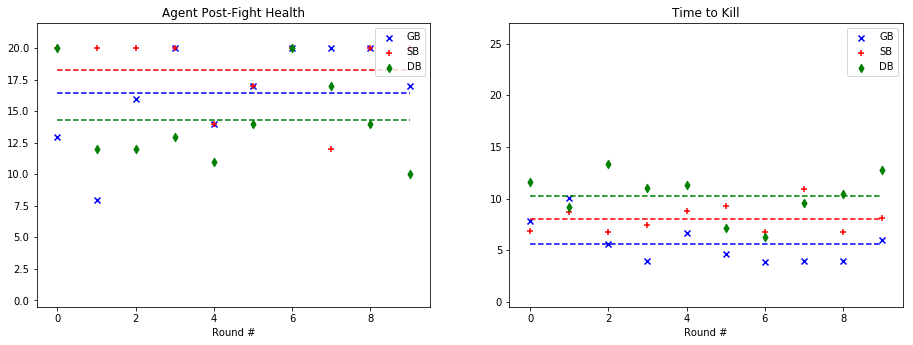

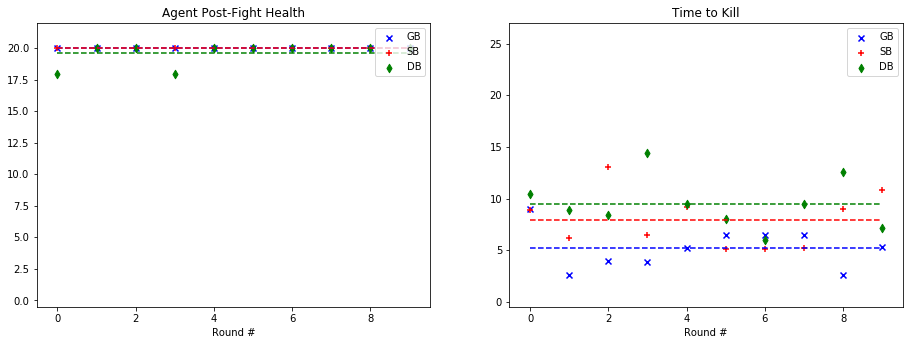

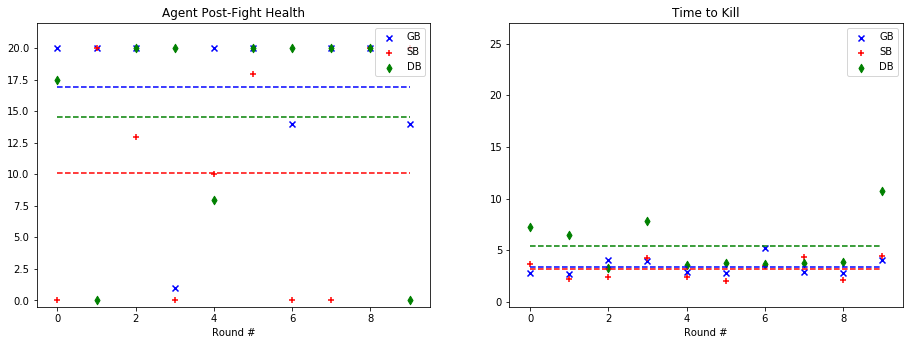

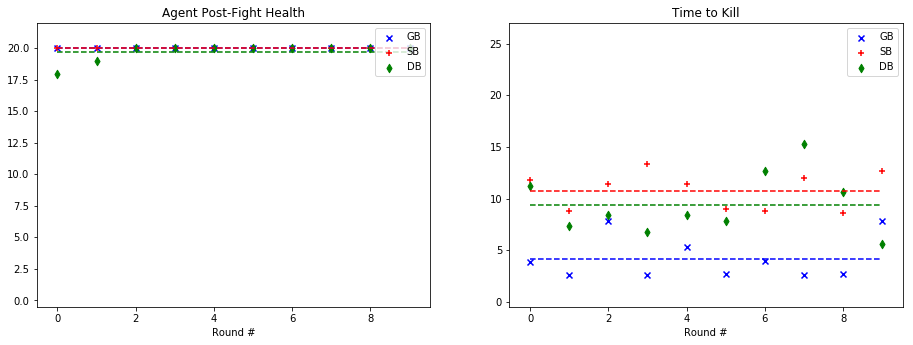

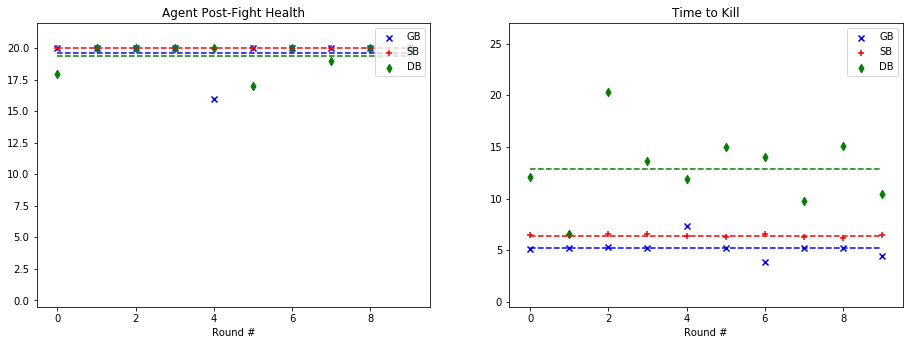

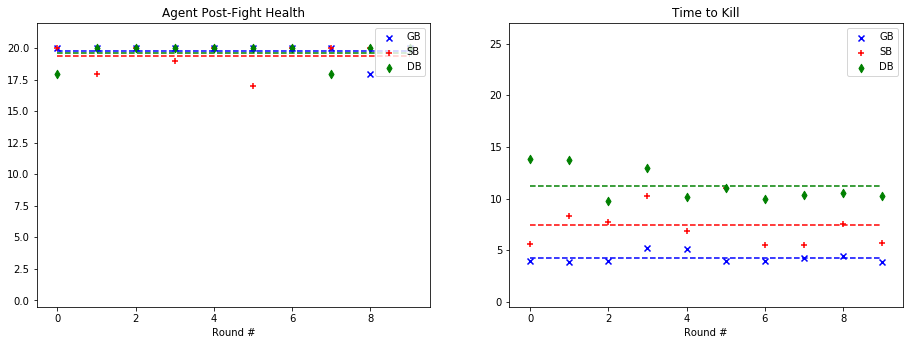

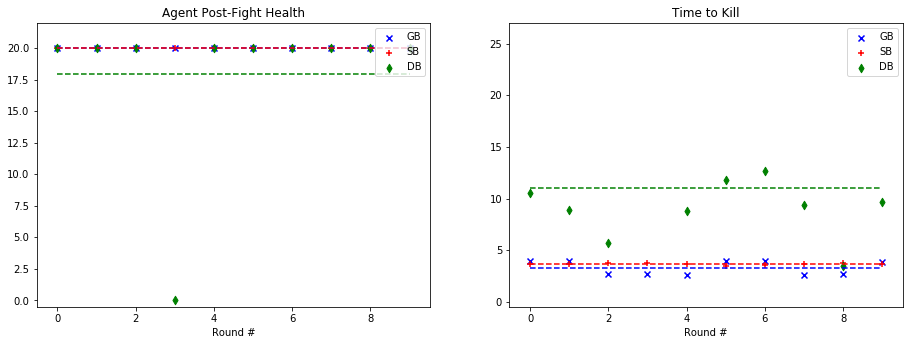

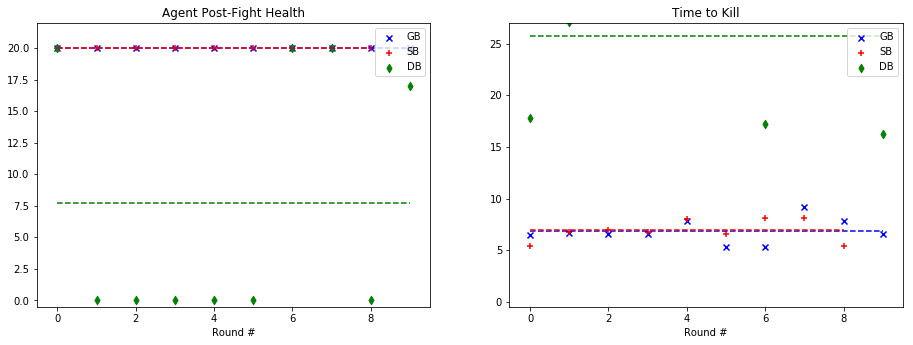

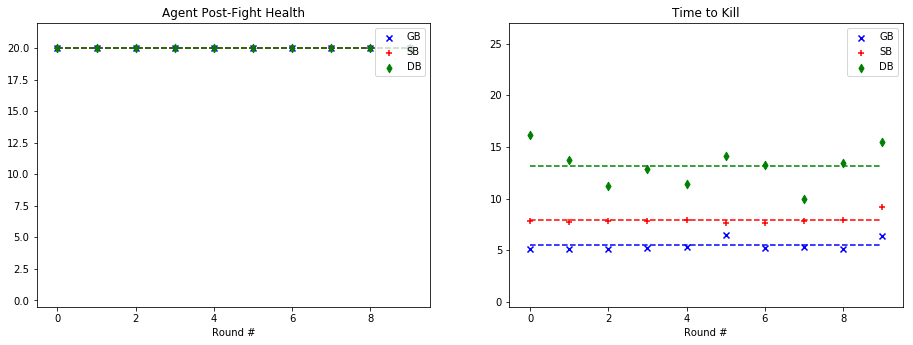

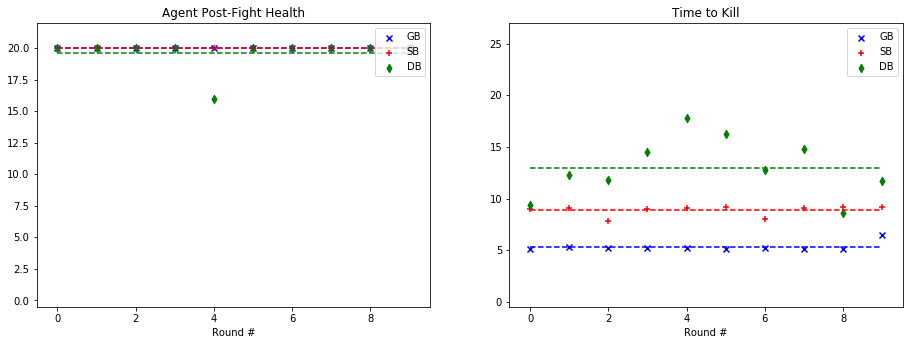

For quantitative evaluation, we used two metrics. At the end of each fight, we checked the health of our agent (‘Agent Post-Fight Health’) and recorded the time it took for the agent to kill the mob (‘Time to Kill’). Each round was capped at 25 seconds long to prevent stalled or drawn-out fights. In the following graphs, we show the statistics for each enemy type in side-by-side graphs. Displayed below is the scatter plot representing the data collected at the end of each fight. The horizontal lines represent the mean of the overall data for rounds with a specific mob type.

Blaze:

Creeper:

Cave Spider:

Endermite:

Ghast:

Silverfish:

Skeleton:

Spider:

Wolf:

Witch:

Zombie:

Zombie Pigman:

Based on the metrics observed in these graphs, our group noticed a considerable improvement from our baseline bot when using a trained model. The graphs on the left, representing the agent’s health, do not demonstrate a decisive improvement with a learned model. While the health of the General Bot and the Specialist are frequently higher than the Dumb Bot, the difference is not always significant. However, noticeable improvement can be seen against the witch, which had been one of the hardest enemies for us to beat originally. The ‘Time to Kill’, representing how long it took the agent to kill the mob, shows a demonstrable improvement in the performance of the trained bots. Just by looking at the average kill times on the graph, it is clear that the Specialist and General Bot usually defeat the mob about 5-10 seconds more quickly than an untrained agent. In fact, the only time the untrained agent beat either of the trained bots in average kill time was against the silverfish. Based on these statistics, training the models had a clear effect on the bot’s ability to kill the different mob types.

As for the comparison between the General Bot and the Specialist, the results were not as we had expected. While the Specialist did learn tailored strategies for each enemy type, as described in the qualitative observations and the video, the general strategy was more effective across the board. For example, in the case of the Ghast, while the strategy of charging and swinging the sword was clearly unique, and in some cases effective, it also often led the specialist to walk straight into fires and burn to death. In other cases, it was able to maintain a similar level of health to the General Bot, but was slower in reaching the goal of killing the mob. However, in one case, fighting the cave spider the Specialist’s tailored strategy led to a slower kill, but allowed it to avoid damage. Therefore, while there was a notable improvement in the performance of both trained bots, the General Bot was the overall winner in terms of performance.

References:

As a guide for giving our bot the ability to aim at the enemy, we used the cart_test.py file in the Python_Examples/ directory of Malmo.

Our main reference for understanding Q-Learning was the class notes and assignment2.py.

Artificial Intelligence: Foundations of Computational Agents